A Value Form, nestled at the intersection of art and perception, plays a pivotal role in crafting depth and dimension in visual compositions. These forms, shaped by gradients of light and shadow, breathe life into flat images, making them appear three-dimensional. Spanning a spectrum from stark contrasts to subtle transitions, various types of Value Forms find their way into myriad artistic endeavors. Dive into the nuances of its definition, diverse manifestations, exemplary application form, crafting techniques, and expert tips to fully grasp its essence.

What is a Value Form ? – Definition

A Value Form, in the realm of art and design, refers to the representation of objects in a way that conveys volume and depth through the variation of lightness and darkness. It’s the gradient of values (shades of gray between white and black) applied to a shape, transforming it from a flat, two-dimensional appearance into a three-dimensional illusion. This manipulation of value helps to suggest depth, volume, and the play of light on the subject, creating a more lifelike and dynamic portrayal in artworks.

What is the Meaning of a Value Form?

The meaning of a Value Form is rooted in its ability to depict depth and dimension in visual art. It encapsulates the idea that, through varying degrees of lightness and darkness, a simple shape can be transformed to appear three-dimensional, giving it volume and substance. The gradation of values – from the brightest highlights to the deepest shadows – mimics the way light interacts with objects in the real world. Thus, Value Form isn’t just about shading; it’s a fundamental concept that artists use to bring depth, realism, and emotion to their work, ensuring that subjects transcend the flatness of the canvas or medium.

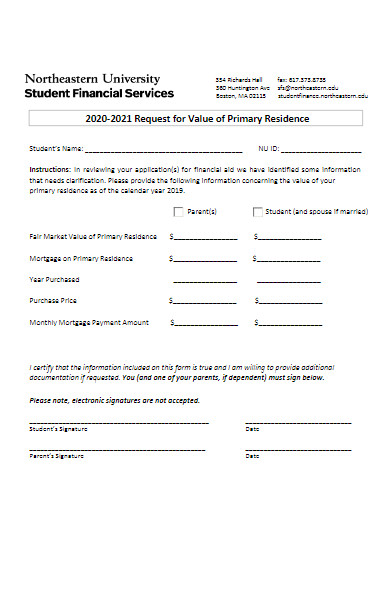

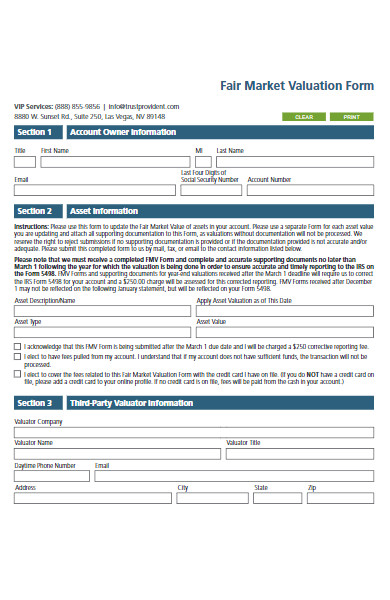

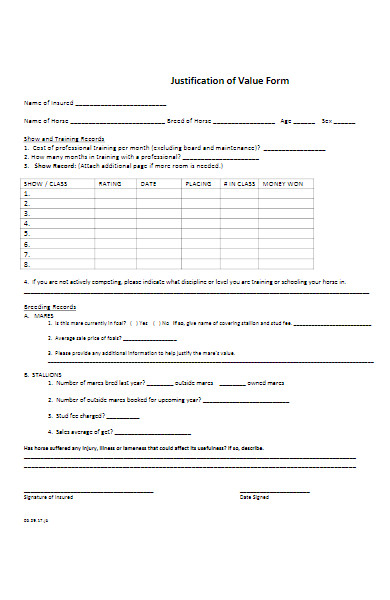

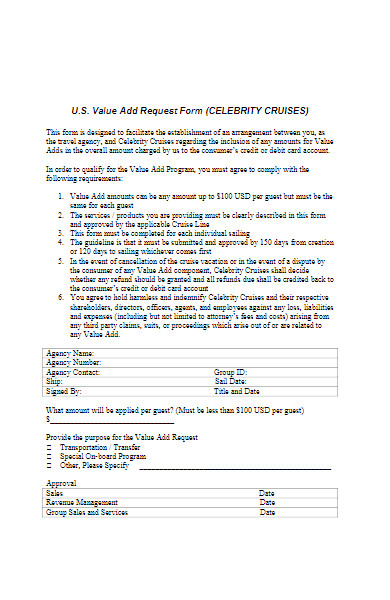

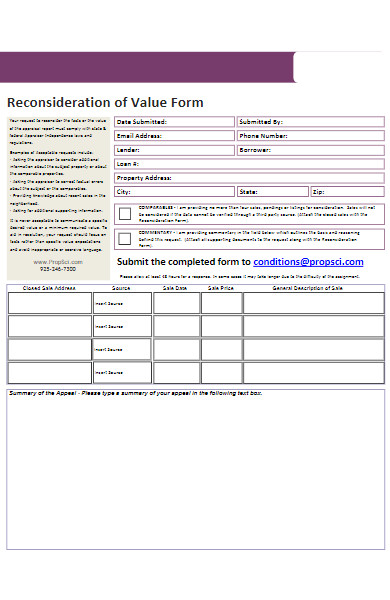

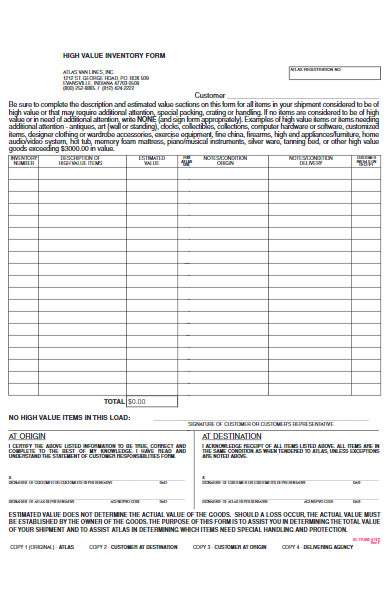

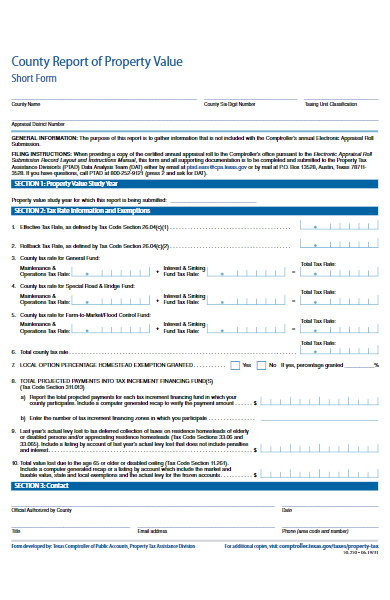

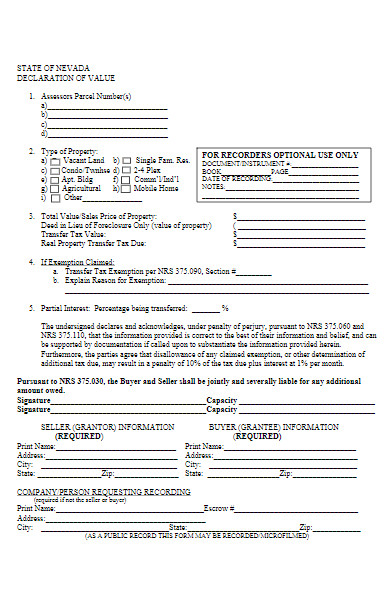

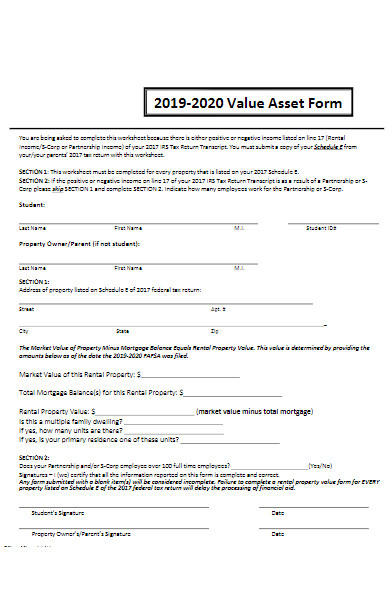

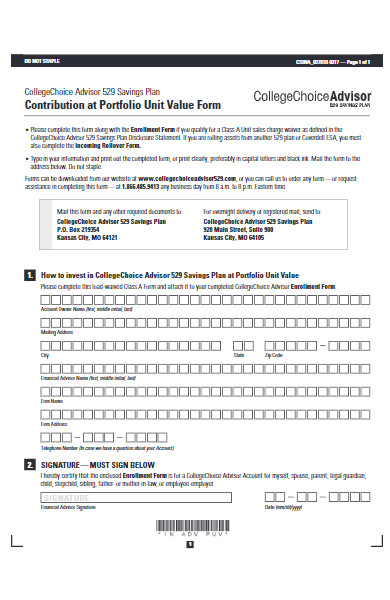

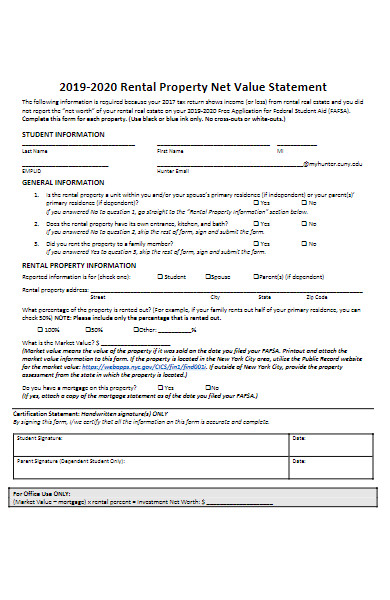

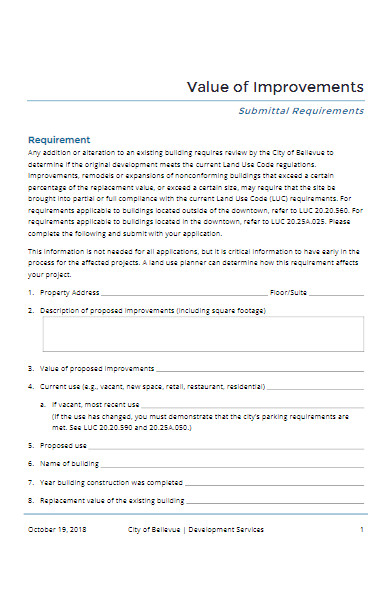

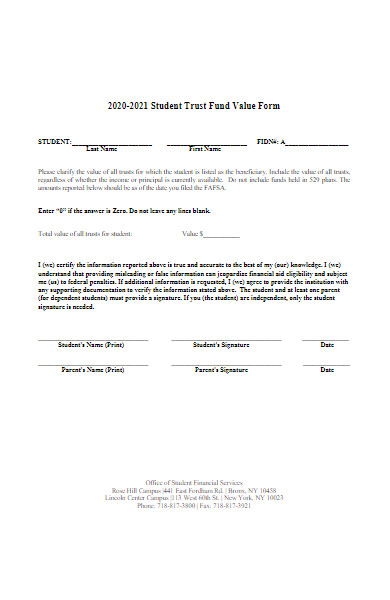

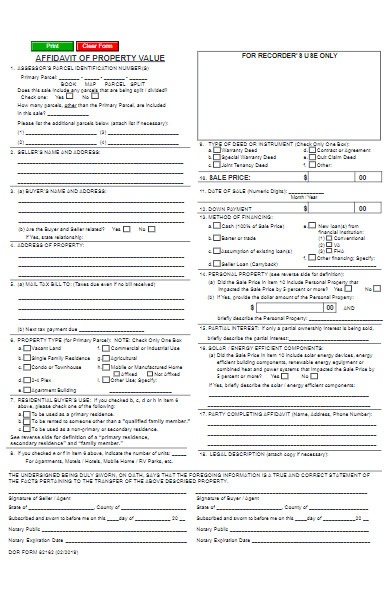

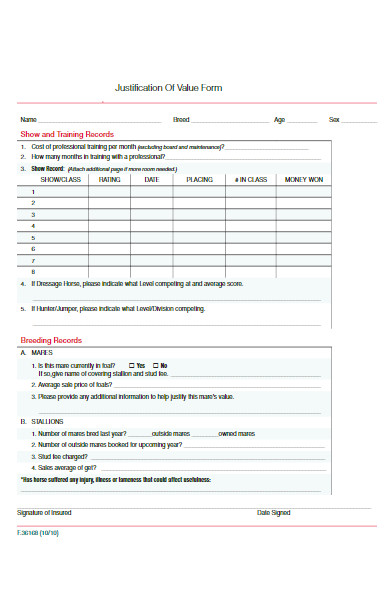

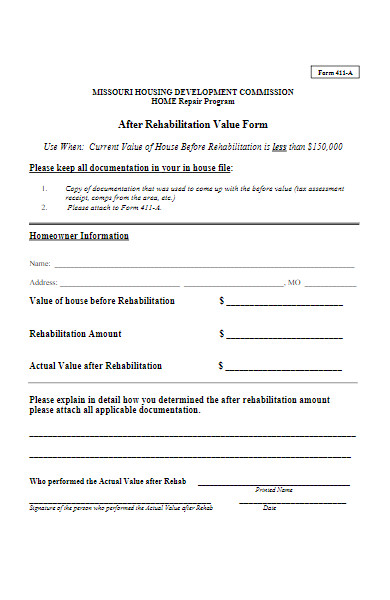

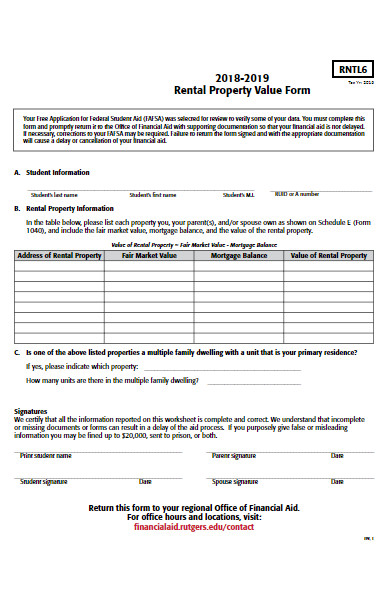

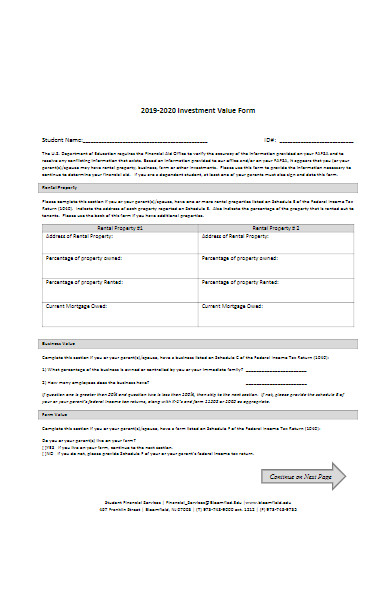

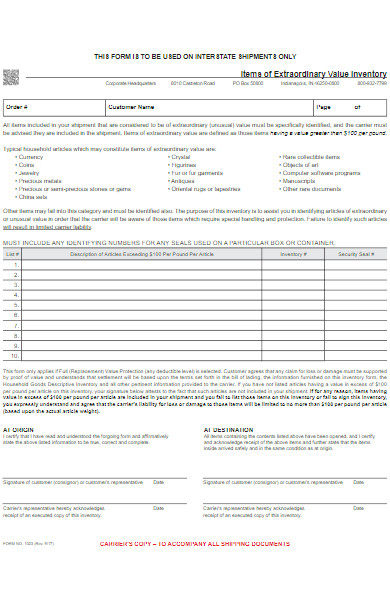

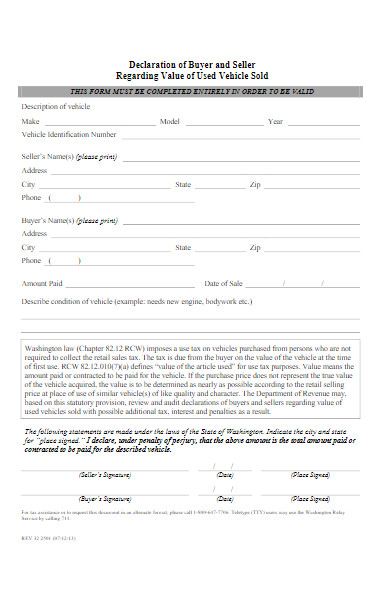

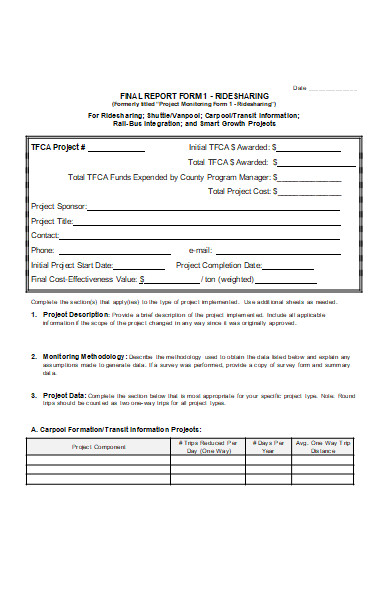

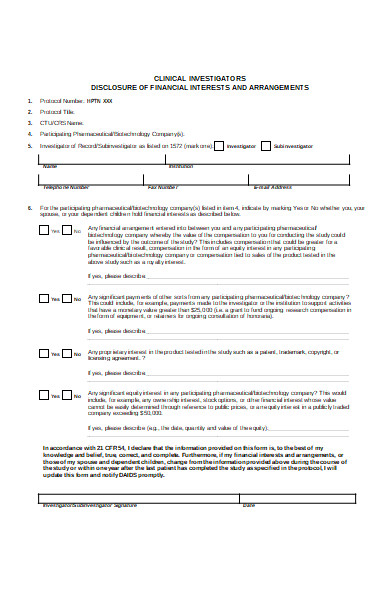

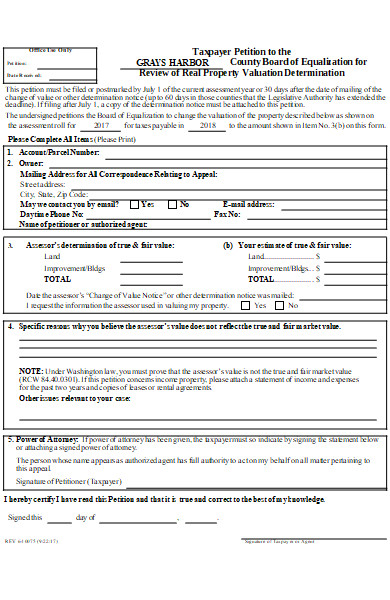

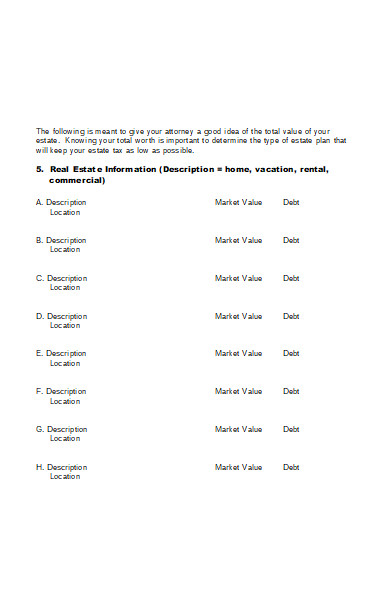

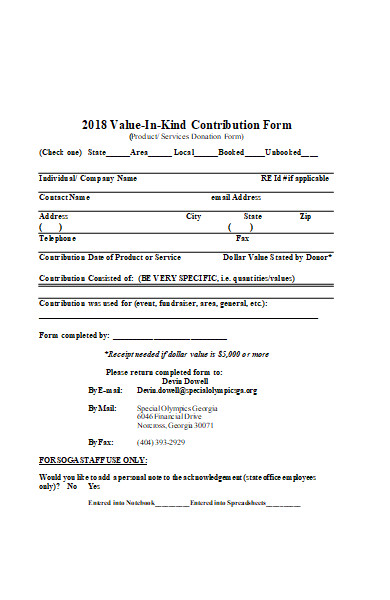

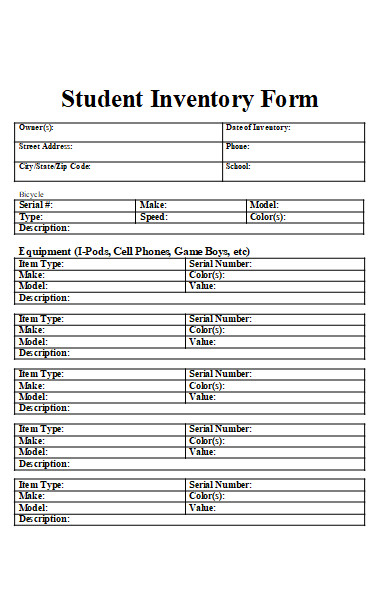

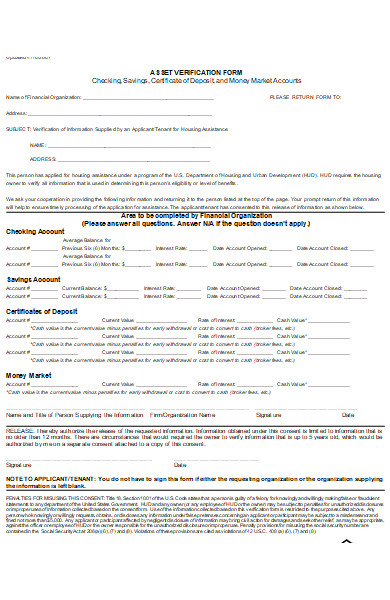

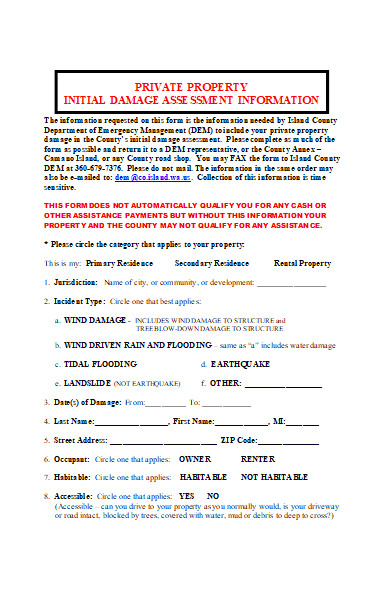

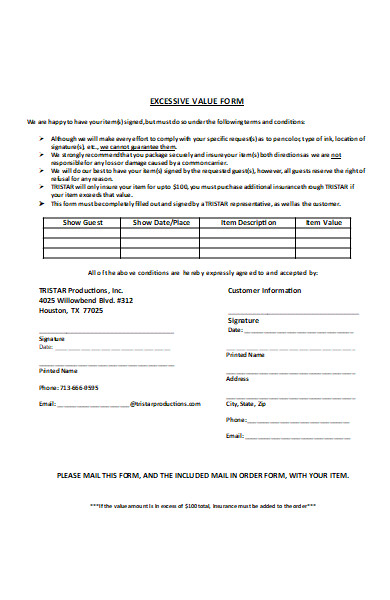

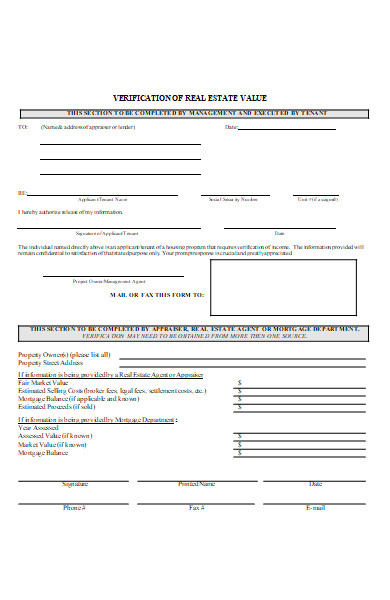

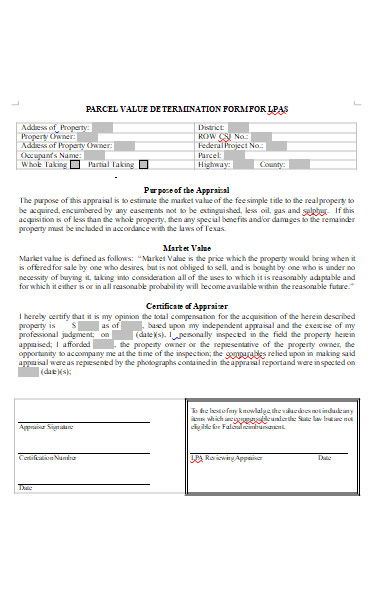

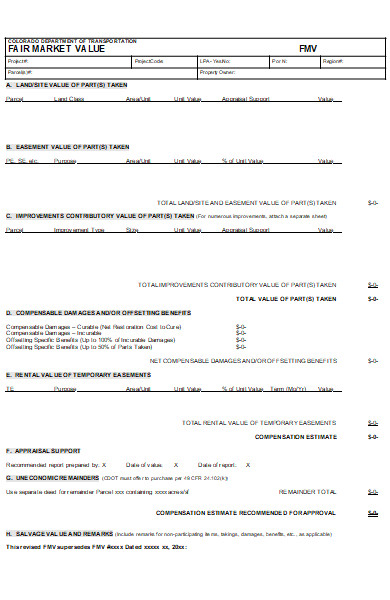

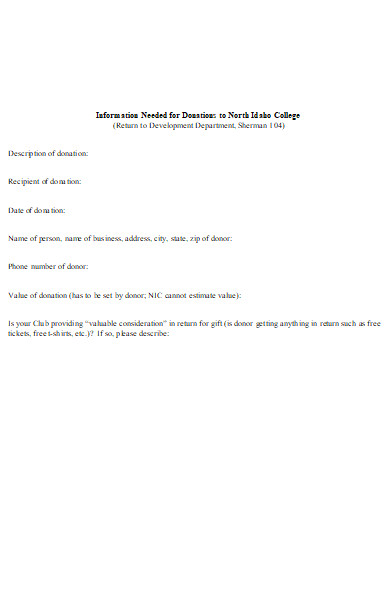

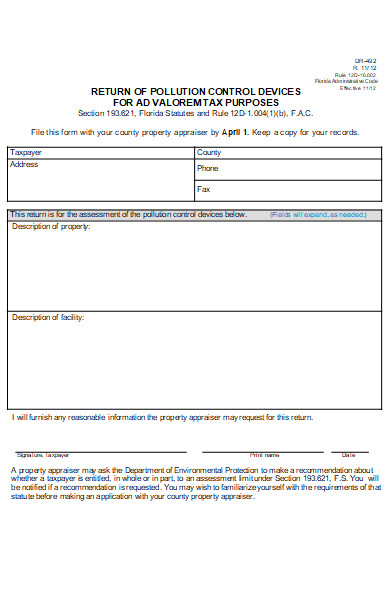

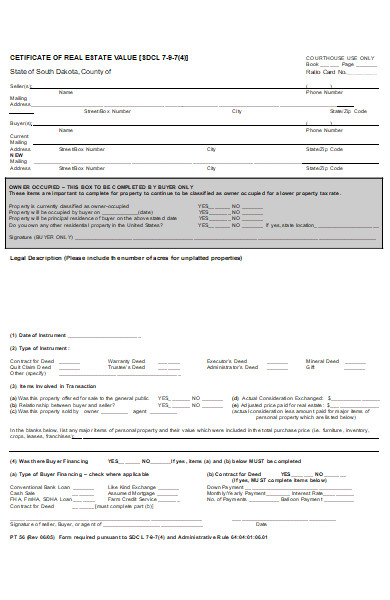

What is the Best Sample Value Form?

-

Clearly Define Your Objectives:

- Before designing a form, be clear about your objectives and what specific information you need to collect. This will help you structure your form effectively.

-

Keep It Concise:

- Shorter forms tend to have higher completion rates. Only ask for information that is absolutely necessary for your objectives. Eliminate unnecessary fields.

-

Use Clear and Simple Language:

- Write clear, concise, and easy-to-understand questions. Avoid jargon or complex language that could confuse respondents.

-

Use a Logical Flow:

- Organize questions in a logical order. Start with simple and non-intrusive questions to build rapport before asking more personal or sensitive ones.

-

Provide Clear Instructions:

- Include instructions or guidelines to help respondents understand how to complete the form correctly. This can reduce errors and improve data quality.

-

Use a Mix of Question Types:

- Utilize a variety of question types, including multiple-choice, yes/no, open-ended, and scale questions, to gather diverse types of data.

-

Test Your Form:

- Before deploying your form, test it with a small group of people to identify any usability issues or confusing questions. Make adjustments based on their feedback.

-

Mobile-Friendly Design:

- Ensure that your form is responsive and can be easily filled out on mobile devices. Many people access forms on smartphones and tablets.

-

Privacy and Data Security:

- Clearly communicate how you will handle and protect the data collected. Ensure that your form complies with relevant data protection regulations.

-

Offer Incentives:

- If appropriate, consider offering incentives to respondents to increase participation rates, especially for longer or more involved surveys.

-

Analyze and Act on Data:

- Once you collect the data, analyze it promptly and use the insights to make informed decisions or improvements.

-

Continuous Improvement:

- Gather feedback from respondents about their experience with the form and use it to improve future iterations.

Remember that the effectiveness of your form or survey depends on your specific goals and the characteristics of your target audience. Tailor your approach to meet the unique needs of your data collection project. You should also browse our property forms.

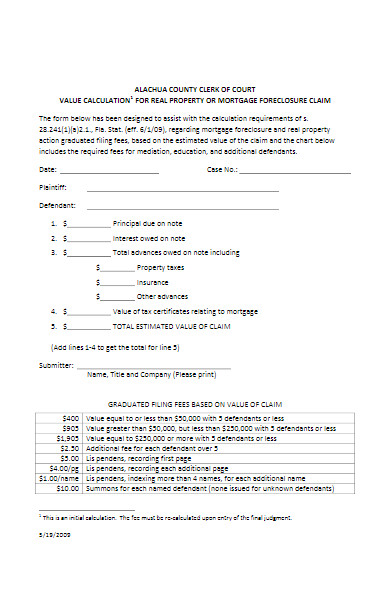

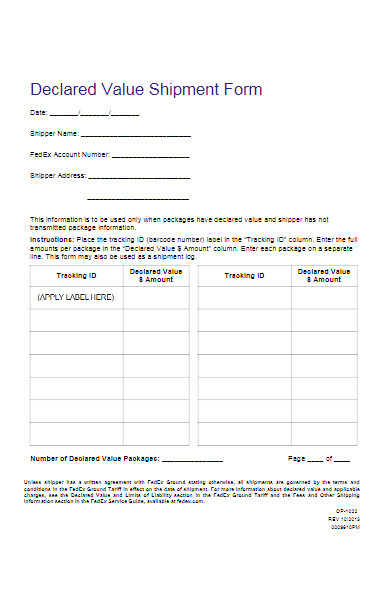

FREE 45+ Value Forms

What is the Value Form theory of Marx?

The value form theory is central to Karl Marx’s critique of political economy and is foundational in his magnum opus, “Capital.” Here’s a brief overview:

- Value and Labour: At the heart of Marx’s theory is the notion that the value of commodities is determined by the amount of socially necessary labor time required for their production. This is often referred to as the “labor theory of value.”

- Commodity Fetishism: Marx argued that in a capitalist society, relations between people appear as relations between things (commodities). This means that the social relationships involved in production are obscured and take on a mystified form.

- Value Form: For Marx, value doesn’t exist in isolation but is represented through a form. The value of a commodity is represented in its exchange with another commodity. In capitalist societies, the primary form of this representation is money. So, the “value form” of a commodity is its monetary expression.

- Simple and Expanded Value Form: Marx discusses different stages in the development of the value form. In its simplest form, one commodity’s value is expressed in terms of another single commodity. However, as trade expands, the value of one commodity is represented in terms of many other commodities. This moves towards a universal equivalent form, where all commodities express their value in terms of one particular commodity.

- Money as the Universal Equivalent: Over time, certain commodities like gold and silver evolved to become the universal equivalent. They took on the role of money. Money, then, is the culmination of the value form, the universal representation of value.

- Abstract and Concrete Labor: While concrete labor produces use-values (the tangible, useful aspect of the commodity), abstract labor (labor in general, devoid of its specific tasks) produces value. It’s this abstract labor that is expressed in the value form.

In essence, the value form theory in Marx’s work is an exploration of how human labor, abstracted from its concrete particularities, gets represented and abstracted further in the form of money, and how this process masks the true social relations of production, leading to commodity fetishism.In addition, you should review our Sample Appraisal Forms.

What are the Forms of Value in Business?

In the business context, forms of value typically refer to the various ways businesses create, deliver, and capture value for their stakeholders, especially customers and shareholders. Here’s a breakdown of several key forms of value in business:

- Economic Value: The tangible financial benefits derived from a product, service, or business activity. This is often measured in terms of revenue, profit margins, and returns on investment.

- Functional Value: Refers to the practical utility or functionality that a product or service provides. It addresses specific needs or problems for the customer.

- Experiential Value: The value derived from the experience of using a product or service. This includes aspects like user experience, brand interactions, and overall customer journey.

- Emotional Value: Relates to the emotional and psychological benefits a customer gains from using a product or service, such as feeling secure, happy, or confident.

- Social Value: The value derived from the social benefits of a product, service, or business activity. This can be seen in how a product enhances one’s social status or how a company’s CSR initiatives positively impact society.

- Cultural Value: The alignment of a product, service, or brand with the cultural values, beliefs, and traditions of a particular group.

- Environmental Value: Reflects the environmental benefits or sustainability of a product or business practice. It’s especially relevant in today’s world, where environmental consciousness plays a significant role in purchasing decisions.

- Innovative Value: The value derived from the novelty or innovative aspect of a product or service, which may offer unique solutions or features not found in existing market offerings.

- Relational Value: Refers to the long-term relationship and trust built between businesses and their customers. Loyalty programs, for instance, aim to enhance relational value.

- Strategic Value: The value derived from assets or actions that provide a competitive advantage in the market, helping a business outperform its competitors.

- Knowledge Value: Refers to the insights, data, and information that businesses obtain from their operations and interactions, which can be leveraged for future strategies and decisions.

Understanding these forms of value allows businesses to diversify their offerings, cater to a broader range of customer needs, and build stronger, more sustainable business models. You may also be interested in our Sales order forms.

What are the two Forms of Value?

In the context of Marxian economics and classical political economy, the two primary forms of value are:

- Use-Value: It refers to the qualitative value of a commodity, i.e., its utility or usefulness in satisfying human wants or needs. Every commodity has a specific use or purpose, whether it’s a tangible item like a car used for transportation or an intangible service like education. The use-value is concrete and varies with different commodities; it’s determined by the physical properties of the commodity and its capacity to serve human needs.

- Exchange-Value: This refers to the quantitative aspect of a commodity’s value, i.e., its value as determined by the relative amount for which it can be exchanged for other commodities in the market. It represents how much of another commodity (or how many other commodities) it can command in exchange. In a capitalist system, the exchange-value is commonly expressed in terms of money, making money the universal equivalent of value. For Marx, the exchange-value of a commodity was rooted in the amount of socially necessary labor time required for its production.

While use-value pertains to the direct utility of an object, exchange-value focuses on its worth in a system of trade. These two forms of value are foundational to Marx’s critique of capitalism, where he argued that the focus on exchange-value over use-value can lead to the alienation of workers and the creation of economic crises. You may also be interested to browse through our other feedback form.

How do Value Forms differ from color forms?

Value Forms and Color Forms pertain to different aspects of visual representation, especially within the realm of art and design. Here’s a breakdown of how they differ:

- Value Forms:

- Definition: Value forms relate to the depiction of objects using varying shades of light and dark, creating an illusion of volume and depth.

- Function: The primary function of value is to show depth and volume in a two-dimensional work of art by simulating how light interacts with objects.

- Application: When artists shade a drawing, they’re working with values. This can be done in grayscale (black to white) or with color, where they consider the relative lightness or darkness of a hue.

- Color Forms:

- Definition: Color forms refer to objects or shapes defined by their color within a composition, which may or may not have value changes within them.

- Function: Color can be used to depict mood, create emphasis, express symbolism, or even guide the viewer’s eye through a composition.

- Application: In a piece with distinct color blocking, where each shape is distinguished purely by its color without any shading, the artist is working primarily with color forms.

While both value and color are integral elements of art, they serve different purposes. Value primarily influences the perception of depth and form, whereas color influences the mood and focal points of a piece. However, in many works of art, value and color are used in tandem, with the value structure often determining the success of the color composition.

Can Value Forms impact perception in design?

Yes, Value Forms can significantly impact perception in design. Here’s how:

- Depth and Dimensionality: Different values can create the illusion of depth in a design. By using gradients and varying shades, a two-dimensional design can give the impression of three-dimensionality.

- Focus and Emphasis: Lighter values can attract the viewer’s attention, while darker values can recede into the background. Designers can use this principle to control where the viewer’s eye goes first and what information they prioritize.

- Mood and Atmosphere: Value can influence the mood of a design. A composition dominated by dark values might convey seriousness, mystery, or melancholy, while a design with lighter values might be perceived as uplifting, airy, or optimistic.

- Contrast: The juxtaposition of light and dark values creates contrast, making designs more engaging and aiding legibility. This is especially crucial in typography where the right value contrast ensures that text is readable against its background.

- Spatial Relationships: Value can define spatial relationships between different elements in a design. Elements with similar values tend to group together in our perception, while those with contrasting values stand apart.

- Texture and Detail: In design, varying values can suggest texture, from the soft gradients of a smooth surface to the abrupt value changes that might suggest roughness or intricacy.

- Harmony and Balance: A well-balanced range of values can bring harmony to a design. Even if there are many contrasting elements, using value effectively can bring them together into a cohesive whole.

- Realism vs. Abstraction: Detailed value gradations can convey a realistic portrayal, while more abrupt and simplified value changes might lean towards abstraction.

In the realm of design, whether it’s graphic design, product design, or even web design, understanding and skillfully manipulating Value Forms is essential. It can transform a flat, uninteresting design into something dynamic, engaging, and effective in communicating its intended message. You should also take a look at our History Form.

Which artists are known for their use of Value Forms?

Many artists across different periods and styles have been recognized for their exceptional use of Value Forms, leveraging the play of light and shadow to create depth, mood, and emotion in their works. Here are some renowned artists known for their mastery of Value Forms:

- Leonardo da Vinci: Known for his sfumato technique, Leonardo used subtle gradations of light and shadow to create soft transitions between colors and tones, giving a dreamy realism to his works like the “Mona Lisa.”

- Caravaggio: A master of the Baroque period, Caravaggio is celebrated for his dramatic use of chiaroscuro (contrast between light and dark) which added intense emotion and realism to his religious subjects.

- Rembrandt van Rijn: His portraits and self-portraits exhibit profound use of value to sculpt the face and clothing of his subjects, creating depth and mood that make his figures seem lifelike.

- Johannes Vermeer: His domestic scenes are known for the delicate interplay of light and shadow, with Value Forms highlighting the texture and material of objects and fabrics.

- Vincent van Gogh: While primarily recognized for his color and brushwork, Van Gogh’s drawings and sketches showcase his understanding of value and its role in defining form and space.

- Edward Hopper: His modern American scenes frequently employ stark contrasts and subtle gradations of value to convey solitude, stillness, and mood.

- M.C. Escher: In his intricate drawings and lithographs, Escher played with value to create optical illusions, blending mathematics and artistry.

- Käthe Kollwitz: The German artist’s powerful prints and drawings often use a deep range of values to convey intense emotion, especially in her depictions of suffering and war.

- Ansel Adams: Though a photographer, Adams’ mastery over Value Forms in his black and white landscapes made each composition strikingly deep and atmospheric.

- Georgia O’Keeffe: Known for her large-scale flower paintings and New Mexico landscapes, O’Keeffe’s use of value brought out the intricate details and forms of her subjects.

These artists, among many others, have shown how mastering Value Forms can elevate artwork, adding depth, texture, emotion, and a sense of realism or abstraction, as desired by the artist. Our Residential Appraisal Form is also worth a look at

Are there specific exercises to practice and improve understanding of Value Forms?

Absolutely! Practicing specific exercises can significantly enhance your understanding and application of Value Forms. Here are some exercises that can help:

- Value Scale Creation:

- Using graphite, charcoal, or paint, create a value scale with at least five to ten steps, transitioning smoothly from the darkest black to the whitest white.

- Ensure there are no abrupt jumps between adjacent values.

- Grayscale Rendering:

- Start by choosing a colored photograph, preferably one with distinct light and shadow areas.

- Reproduce the photograph in grayscale using your chosen medium, focusing on capturing the various values.

- Sphere Shading:

- Draw a circle and imagine a light source direction.

- Shade the sphere to show the highlight, mid-tones, core shadow, reflected light, and cast shadow.

- Still Life Drawing:

- Set up a still life arrangement with objects of different textures and shapes.

- Use a single light source to create defined shadows.

- Draw or paint the arrangement, focusing on the values.

- Value-Based Composition:

- Create a piece using only two values: black and white.

- Gradually increase the number of values in subsequent pieces, noting how added values influence perception and depth.

- Monochromatic Painting:

- Choose a single hue and create a painting using only variations in value of that hue. This helps separate value understanding from color.

- Negative Space Drawing:

- Focus on drawing the spaces around and between objects rather than the objects themselves. This helps emphasize the importance of shadow values.

- Thumbnail Sketching:

- Create small, quick sketches focusing on value distribution in various compositions. This is great for planning larger pieces.

- Value Inversion:

- Take a completed grayscale artwork or a photograph.

- Invert the values (either manually by re-drawing or digitally). This exercise challenges your understanding of light logic.

- Observational Drawing:

- Regularly draw from life, focusing on how light interacts with different surfaces and forms.

- Limiting Your Values:

- Force yourself to create a piece using only three to four values. This helps in understanding the importance of each value range and its impact on the composition.

- Texture Exploration:

- Draw various textures (like fur, metal, glass, water) using value. This will hone your ability to depict different materials through shading alone.

For best results, consistency is key. Dedicate regular time to practice, and over time, your understanding and mastery of Value Forms will deepen. Additionally, reviewing and analyzing the works of artists known for their use of value can provide further insights and inspiration.

How do Value Forms interplay with light sources in a composition?

Value Forms and light sources are intrinsically linked in a composition. The way light interacts with objects determines the values we see, which in turn defines the form, depth, texture, and mood of the composition. Here’s an exploration of their interplay:

- Direction of Light: The position of the light source in relation to the object affects the distribution of values. Common light directions include:

- Frontal lighting: Illuminates the front of the subject, often flattening features and minimizing shadows.

- Backlighting: Creates silhouettes and emphasizes the form’s edges.

- Side lighting: Highlights texture and produces strong value contrasts.

- Top lighting: Often results in strong shadows beneath the subject, giving a dramatic effect.

- Underlighting: Casts upward shadows, often used for eerie or dramatic effects.

- Intensity and Quality of Light: The strength and type of light affect the range and transition of values.

- Hard light: Produces sharp, distinct shadows with high contrast between light and dark values.

- Soft light: Offers smooth transitions between light and shadow, with softer edges and less contrast.

- Highlight: The area where light directly hits an object will often be the lightest in value, representing the brightest spot.

- Mid-tones: These are the intermediate values on the object, representing areas that receive some light but aren’t directly illuminated or in shadow.

- Core Shadow: This is the darkest part of the shadow, where the object receives the least amount of light due to its form blocking the light source.

- Reflected Light: Light can bounce off surrounding surfaces and illuminate parts of an object that aren’t directly exposed to the primary light source. This area is lighter than the core shadow but darker than areas directly illuminated.

- Cast Shadow: This is the shadow projected by the object onto surrounding surfaces, away from the light source. Its softness or hardness, length, and value depend on the light source’s quality and distance.

- Ambient Occlusion: In areas where two forms meet and block light from penetrating, there is a concentrated shadow. It’s a subtle effect but crucial for realism.

- Atmospheric Perspective: In landscapes or scenes with depth, the interplay of light and air particles can cause distant objects to appear lighter in value and less saturated, adding depth to the composition.

- Translucency and Transparency: In objects like glass or water, light doesn’t just reflect off the surface; it passes through and bends, creating intricate patterns of value.

- Specularity: Shiny or glossy surfaces have intense, focused highlights due to their reflective nature. The value contrast on such surfaces is often stark.

Understanding the interplay between Value Forms and light sources is foundational in art and design. It enables artists to render objects realistically, convey depth, create mood, and guide the viewer’s attention within a composition. Whether one is working in a hyper-realistic style or a more abstract manner, knowledge of this interplay shapes how forms are perceived and interpreted. In addition, you should review our Community Forms.

How to Create a Value Form?

Creating a Value Form involves understanding and rendering the interplay of light on a subject to depict its three-dimensional quality on a two-dimensional surface. Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you create a Value Form:

-

Choose a Subject and Light Source:

- Decide on an object or subject you want to depict.

- Determine the direction and quality (hard or soft) of your light source. This will influence the shadows and highlights on your subject.

-

Sketch the Basic Shape:

- Start with a simple line drawing of your subject, focusing on its overall shape without adding details.

-

Establish the Highlight:

- Identify the area on your subject where the light source directly hits. This will be the brightest area or the highlight.

-

Identify the Mid-tones:

- Mid-tones are the values between the darkest shadows and the brightest highlights.

- Shade these areas lightly, ensuring you leave the highlight areas untouched.

-

Add the Core Shadow:

- On the opposite side of the highlight (away from the light source), add the darkest area, known as the core shadow.

- This is where the object receives the least amount of light.

-

Render Reflected Light:

- Just beside the core shadow, and before the object’s edge, you might notice a slightly lighter area, especially if the object is placed near other surfaces. This is reflected light.

- Shade this area lighter than the core shadow but darker than the mid-tones.

-

Draw the Cast Shadow:

- Depending on your light source direction, draw the shadow that your object casts on the ground or on other surfaces.

- This shadow’s edge can be soft or sharp, depending on the light’s quality.

-

Blend and Smooth:

- Using a blending tool (like a blending stump, your finger, or a soft brush), smooth out the transitions between different values to create a gradient effect.

-

Adjust Contrast:

- If necessary, deepen the shadows and brighten the highlights to increase the contrast, making the form appear more three-dimensional.

-

Add Details:

- With the basic values in place, you can now add finer details to your drawing, paying attention to how light interacts with these smaller features.

-

Evaluate and Adjust:

- Step back and review your drawing. Adjust any areas that need more depth or correction.

-

Practice with Different Textures:

- As you become more comfortable with value forms, practice rendering different textures (e.g., glossy, matte, rough, smooth). This will challenge your understanding of how light interacts with varied surfaces.

Remember, the key to mastering Value Form is practice and observation. Regularly sketching from life, studying the way light interacts with objects around you, and understanding the science of shadows and reflections will enhance your skills over time.

Value Form is pivotal in art, translating three-dimensional reality onto a two-dimensional plane by harnessing light and shadow. From understanding its foundational meaning to mastering diverse types and examples, artists use Value Form to convey depth and realism. Embracing the nuances of creation and the accompanying tips ensures that art has depth, texture, and an essence of realism. You may also be interested in our Affidavit Form .

Related Posts Here

-

Accident Statement Form

-

Performance Review Form

-

Event Contract Form

-

Contest Registration Form

-

Waiting List Form

-

Restaurant Schedule Form

-

Mobile Home Bill of Sale

-

Landlord Consent Form

-

60-Day Notice to Vacate Form

-

Financial Statement Form

-

Product Evaluation Form

-

Construction Contract

-

School Receipt Form

-

Restaurant Training Form

-

Daily Cash Log